Meters

Basics of Meter

meter is a recurring pattern of stresses or accents that provide the pulse or beat of music. Meter is notated at the beginning of a composition with a time signature. Time signatures are always notated with two numbers, one on top of the other, much like a fraction in math. The top number denotes the number of beats in each measure. The bottom number denotes the note value that receives the beat. The note values that can receive beats include double whole note, whole note (1), half note (2), quarter note (4), eighth note (8), sixteenth note (16), thirty-second note (32), sixty-fourth note (64), and one hundred and twenty-eighth note (128).

Meter Classification

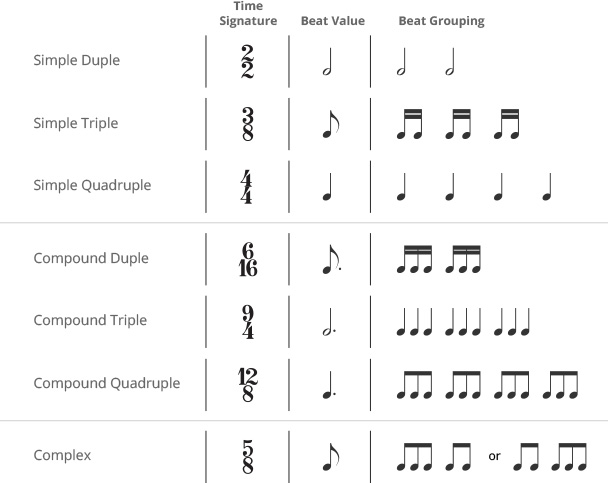

Meter can be categorized as simple, compound, or complex. These three categories can explain all rhythmic patterns in Western music. Each of the categories of meter is defined by the subdivision of beats. The number of beats per measure determine the term associated with that meter.

Beats Per Measure

Term

2 or 6

3 or 9

4 or 12

everything else

Simple Meter

Simple meter (simple time) can be defined as a meter where each beat in a measure can be subdivided by two.

Compound Meter

Compount meter (compound time) can be defined as a meter where each beat in a measure can be subdivided by three. It is commonly distinguished by dotted note.

Complex Meter

Complex meter (complex time) can be defined as a meter that does not fit into the usual duple, triple, or quadruple categories, including most odd numbers and unusual beats per measure.

Meter in Relation to Tempo

All indications of meter are subject to the interpretation of the composer and of the performer. In realizing their musical ideas, composers need to work within the existing notation, augment the existing notation, or create new notation. Although creating new notational systems were popular in the first half of the twentieth century, the problems they created often exceeded the value of the composition and are not commonly used. Therefore, it is not uncommon for composers to create music using existing notation that is perceived as being inconsistent with what is performed.

When the tempo (or speed) of the music is very slow or very fast, the beat can be perceived as being different from the meter as notated. An example of a fast tempo would be a Viennese waltz where the meter is shown as 3/4 (with 3 beats per measure and the 4 or quarter note getting one beat), but this style of waltz is performed so quickly, it is perceived as being performed with one beat per measure. The written meter is still correct, only the performance of the composition gives the perception of something different.

Similarly, when a composition is performed very slowly, the listener can often hear (or feel) twice the number of beats than are notated. With extremely slow music, it is often difficult to hear any beat or pulse.

Also, some compositions, such as some fantasias, have no measures and provide only the basic meter and note values. This allows the performer to freely interpret the composition and decide how fast or slow to perform each phrase. The meter only provides a basic guide to the relationship of one note value (or length) to the next. Thus, no two performances or interpretations will be exactly the same and there is no possibility of perceiving any meter at all.